Stilt Sandpiper (Calidris himantopus)

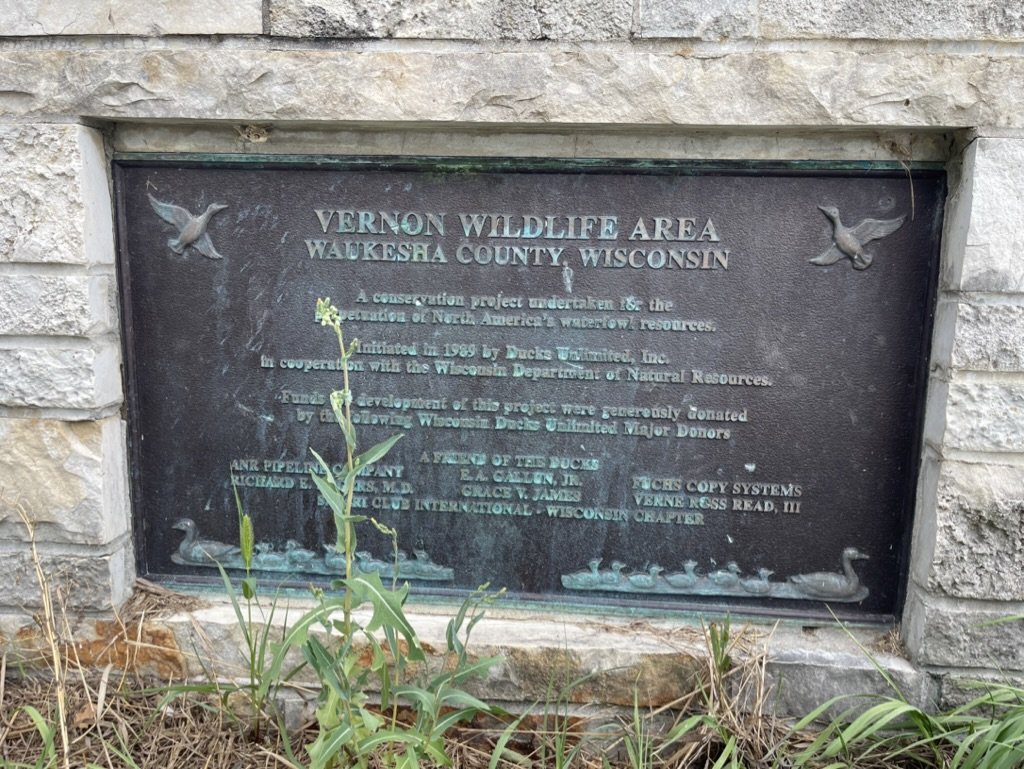

Vernon Marsh Wildlife Area

Waukesha County, Wisconsin

August 13th, 2023

Birders often divide the year not by the seasons, but by distinct migration patterns. The most famous, of course, is spring migration, highlighted, at least in Wisconsin, by the brief sojourn of a myriad warblers in the region. Accompanying these warblers are other songbirds, as well as, among others, shorebirds and raptors. This migration, ultimately, is short-lived, and thus begins the somewhat calm, uneventful summer.

If there is a spring migration, there has to be a fall migration. Even though this phenomenon is not as colorful, as breeding birds have already ventured north to “do their business” and are heading back south to ride out the winter, the fall can be just as exciting. Yes, warblers do come back, but now it’s the shorebirds’ turn!

****

I often don’t see shorebirds during the spring. This may be related to their decision to follow the well established flyways along either coast or cruise above the Mississippi. Southeastern Wisconsin isn’t necessarily their destination, except for Wilson’s Snipes and Killdeer. In fact, many shorebirds venture to the roof of the world on the tundra of Alaska and Canada. During the fall, flyways are not often followed as stringently, so species who would otherwise avoid my area stop briefly for rest and refreshments.

What’s the avian equivalent of Kwik Trip? The most famous would be Horicon Marsh or Necedah National Wildlife Refuge. Another option for their weary travelers is the Vernon Marsh Wildlife Area near Mukwonago.

Apparently, I went to Vernon Marsh once before when I was a young child., when my dad took me fishing. All I can remember is mud and mosquitoes. I’m not even sure if we got any fish.

***

We arrived around 8am in the parking lot at the end of Frog Alley, from where we descended the short hill along a prairie that opened into a flood plain. A grassy trail wraps around and leads to what now amounts to an impoundment. Along the way, several swallows, Cedar Waxwings, and a Rose-breasted Grosbeak flew overhead. By the time we reached the water, Green Herons took flight for the nearby riparian woodlands.

Two birders who arrived (much) earlier were walking back to their cars and stopped for a chat. Efficient and to the point—after the obligatory how-do-you-do greetings, of course— they shared the highlights of their morning. Notably, they failed to see what I had come there to find: Stilt Sandpiper.

****

For all the names given to shorebirds, stilt may be the most nebulous. Aren’t all shorebirds, to some extent, walking on long, stilt-like legs as they forage in the shallow waters and thick mud? The ornithologist in charge that day must have been lazy and assigned the obvious to this bird.

At any rate, the Stilt Sandpiper, or Calidris himantopus, is a true long-distance traveler. It spends its winters as far south as Argentina, and returns for the summer to the arctic. Its life history has only been recently studied, according to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, with serious study available in only a few locations along its breeding range. What is know to some extent is its migration patterns. In spring, as it flies north, the Stilt Sandpiper will travel across the Great Plains. During fall, it will travel over water to the Caribbean and northern South America, with the periodic stop in the Midwest.

Though fairly uncommon, it is considered a species of “Least Concern”. Thank goodness.

****

No sooner when I set up my Peak Design travel tripod and Kowa TSN-99A spotting scope did a curious Marsh Wren pop out from the reeds to say hello. Usually quite secretive, this wren may have been wondering who was invading its territory. I expressed some kind words in pishing to return the greeting. He looked around before dipping back into the reeds.

****

Before going on, I would like to mention a not unpopular mantra about shorebird identification. It’s hard! In fact, it can be downright infuriating! Except for the easy species like the Killdeer, many sandpipers or plovers look extremely similar, that even with a great field guide and years of experience, one would be hard-pressed to say he completely knows them. I am by no means an expert, and today would prove to be an exercise in breaking down field identification by the most minute features. Height, bill length, foraging pattern, color of the supercillium—quantum mechanics is easier that this, and that’s coming from a humanities major!

Fortunately, I would keep my sanity, at least until I got home and went through photos again to invite further second-guessing. On the bright side, this conundrum gives me inspiration for another blog post, so please stay tuned for that.

:)

****

Scanning across the mud flats yielded the usual suspects: Killdeer, Great Blue Heron, Green Herons, Canada Geese, and two Trumpeter Swans in the distance. Finding the smaller, interrupted bodies of water, we could see Yellowlegs and sandpipers. No other plovers were there today.

After seeing my six Greater Yellowlegs (or was it a Lesser?), I saw a sandpiper that didn’t quite fit with the others. Tall and lanky, with a beak heavier than I expected, white supercilium, some red on its head, and a scaly pattern on its wings? Could this be what I came here to see?

Yes it was!

****

Typically, the Stilt Sandpiper will primarily eat invertebrates and seeds, but will wade into belly-deep water to probe for food and small organisms in the soft mud. Its feeding behavior is characterized as pecking, probing, and stitching, by which it rabs rapidly as it moves in the water. The sandpiper will often submerge its head into the water in search of tasty morsels.

During migration, Stilt Sandpipers may be found with other shorebirds. This can be either a handy tool in the field for picking out the species from a crowd, or annoying. For me, it was truly beneficial.

To illustrate my point, here is the Stilt Sandpiper alongside Yellowlegs, one Greater and the other Lesser.

Compared to either Yellowlegs species, the Stilt Sandpiper is notably smaller, about 2-5 inches shorter. The Stilt displays a prominent white supercillium or “eyebrow”. Its plumage is accentuated by a scaly pattern of dark splotches on its wings. The wingtips stop just before the end of the tail. Its bill is notable for a decurved tip.

Looking at these photos, I wonder if this may be a juvenile on its first journey south, or a molting adult. Adults in their breeding plumage will have heavier barring on their bellies, but this one has less so. That said, it does have the other hallmarks of a Stilt.

****

Satisfied, as well as hungry and tired from the rising sun and warming August temperatures, we returned to the car. Yes, there were other sandpipers, but I feel I should review my eBird checklist before commenting further on that. I did, however, see a Short-billed Dowitcher!

****

If the different types of birding can be characterized into literary genres, then shorebird-ing has to be a bildungsroman. I am but a novice with these wonderful creatures, but I am still learning. Eventually, and with practice, I hope to be comfortable in my muddy hiking boots by the edge of the pond and say, with complete confidence, all the different species I see out there foraging and running around on the flats. Until then, I will consult the experts and grow as a birder.

Happy birding!

Copyright for the media within this post belongs solely to me.

If you enjoy my posts with their witty, thoughtful, and (sometimes) funny discussions, please feel free to follow me for more!

The optics used for these images include:

Canon mirrorless EOS R 100mm-500mm F4.5-7.1 L IS USM RF lens with the 1.4x extender.

iPhone 12 Pro Max with Kowa TSN-99A scope.

Short Bibliography:

birdsoftheworld.com

Sibley

Peterson

The Shorebird Guide by O’Brien, Crossley, and Karlson